Reproducibility in ML: Why Your Results Don’t Match | Best Practices 2025-26

Introduction: The Unseen Problem in Your Study

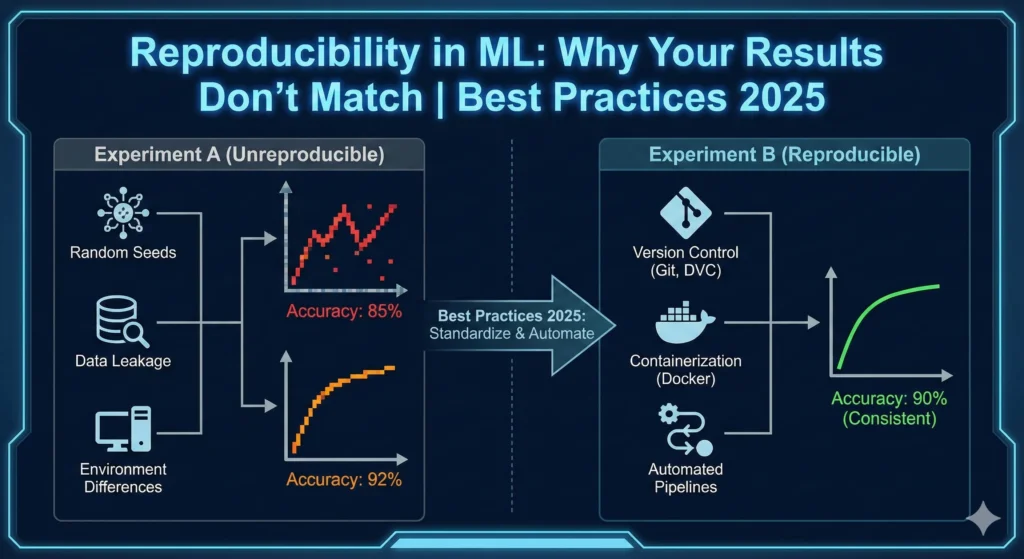

You spend three weeks carefully following the steps in a published paper. You get their dataset, set the same hyperparameters, and run their code. But something is wrong. What they said doesn’t match what you found.

You mix things up. You try different seeds at random. You look at the versions in the library. Nothing. The accuracy drops by 5%. The F1 score changes in a way that isn’t normal. And then you realize with a sinking feeling that you just went through what millions of researchers are going through right now.

This isn’t about being careless. It’s not about not being good at something. Welcome to the machine learning reproducibility crisis. Researchers who are very careful don’t always get the same results, and sometimes they can’t even get the same results from their own work from a month ago.

The problem is that it is costing the whole field billions of dollars in wasted computing power, duplicated research, and broken trust. The worst part is? A lot of people don’t even know it’s happening.

This post will show you:

We’re going to talk about why ML doesn’t work (hint: it’s a lot more complicated than just forgetting a random seed), look at the real human and financial costs, go over some real-life examples of when it went wrong, and most importantly, show you exactly how to avoid becoming another statistic in this crisis. By the end, you’ll know not just the “why,” but also the “how”—the exact steps you can take to make your ML work reproducible.

Part 1: What Is the Problem with Reproducibility?

What Does It Mean to Be Able to Be Reproduced?

Let’s start with the basics since this word is used a lot. In machine learning, reproducibility means that you get the same results every time you run the same algorithm on the same dataset in the same environment and with the same settings.

A lot of people think that reproducibility and replicability are the same thing, but they are not. Consider it this way:

Reproducibility: You should get the same results if you have the same code, data, and environment.

Replicability: Means that you can use different data, methods, and settings and still get the same results.

Things have to be able to be done again for science to work. You can’t learn from results that you can’t see.

Levels of Reproducibility: From Description to Full Experimentation

The framework for reproducibility above shows four ways that research can be reproduced. Most of the papers that have been published are either R1 (just a description) or R2 (code without any information about the data or the environment). R4, the highest level, needs everything: the full experimental setup, environments that can be repeated, all data, and documented dependencies.

How bad is this?

In 2016, Nature sent out a survey to more than 1,500 researchers. The results were very unexpected. More than 70% of the scientists said they had tried and failed to get the same results as another scientist. But here’s the kicker: more than half of them couldn’t even do the same experiments they had done weeks or months before.

Nature 2016 Survey: How Researchers Handle Reproducibility

This wasn’t just happening in one place. When the numbers were broken down by field, they stayed stubbornly high: 87% of chemists, 77% of biologists, 69% of physicists, and 67% of medical researchers all said they couldn’t reproduce their results.

The term “reproducibility crisis” became very popular after Ali Rahimi’s controversial NeurIPS talk in 2017. In that talk, he said that ML research had become “alchemy”—lots of intuition, lots of luck, and not enough rigorous science. The speech got everyone in the community excited.

Part 2: Why Your ML Results Don’t Make Sense

The Real Culprits (It’s Not Just Random Seeds)

Most people think that problems with reproducibility are simple. You only need to set a random seed, a numpy seed, and a torch seed to get started, right? Nope. That’s like believing that changing the oil will fix a broken transmission.

Barrier #1: Not Keeping Track of Experiments (The Silent Killer)

This is the worst thing that could happen. It is almost impossible to do experiments again if ML teams don’t write down their inputs and new decisions.

Think about what happens in a normal ML process. You change the hyperparameter to see what happens. It doesn’t work. You change how quickly you learn. Not very good yet. You change how big the batch is. A little bit better. You change the function that activates it. That’s good enough.

But you probably forgot to write this down:

What version of TensorFlow or PyTorch you have

The exact steps you took to get ready

If you standardized or normalized the data,

The ways you added more data

What samples you used to train your model

How you handled values that weren’t there

If you chose any features

These are all “silent” choices that your code makes, usually through default parameters in libraries. It’s easy to forget about them when you write up your method. But any one of them can have a big effect on your results.

Only 6% of researchers at the best AI conferences make their code available to the public. That means that 94% of papers are at reproducibility level R1 or R2. This means that they only have descriptions and maybe some code, but not the whole experimental setup.

Barrier #2: GPU Non-Determinism (The Hardware Betrayal)

Even if you set all of the random seeds correctly, your GPU may still give you different results each time you run it. This should make you scared.

Here’s why. Modern GPUs don’t care about order. Floating-point operations are important because of how computers round numbers and keep track of them. They make operations as fast as they can. When you use parallelization, you might get slightly different results when you add numbers in a different order. This is because floating-point numbers aren’t always accurate.

A 2020 study found that almost 74% of the standard deviation in ResNet results on GPUs was due to random events that happened on the GPU, not because of different initializations or batch orderings.

When you set seeds right, GPU parallelization means:

The same code, data, and setup don’t always give the same results.

Researchers at mlf-core found that just setting random seeds wasn’t enough to get consistent results in GPU calculations. You need to turn on more deterministic settings in PyTorch or TensorFlow, but this usually makes things go slower.

Barrier #3: Changes in Training That Are Not Planned (The Math Problem)

Machine learning models include randomness. They rely on randomization at various junctures:

Setting up random parameters (different starting weights)

Stochastic gradient descent (picking samples to learn from at random)

Taking random data in groups and mixing it up

Dropout and other regularization methods that add noise on purpose

This isn’t a mistake; it’s a part of the design. Adding randomness to models helps them make predictions that are more general and don’t get stuck in local minima. But it also means that two training runs that are exactly the same will almost never give the same results.

Barrier #4: Data leaks and errors in the way things are done

Sometimes, reproducibility doesn’t work because the first experiment had a mistake that no one saw.

Check out the Princeton study on how machine learning can be used in political science. Researchers attempted to replicate four published studies that asserted the superiority of ML methods. They found a big mistake in each of the codes when they looked at them more closely: data leakage.

Researchers in one study (Muchlinski et al.) filled in missing values in both the training and test sets before splitting them. This meant that information from the test set got into the training process, which made the performance metrics look better than they really were. When they were fixed, the advanced ML models were no better than simple logistic regression.

These scientists were not careless. These were published in journals that are among the best. These reviewers had said yes. But the method had some big problems that only showed up when people tried to use it again.

Barrier #5: The Issue of Hyperparameter Sensitivity and Exploration

Here’s a sneaky problem: researchers often test a lot of different hyperparameter combinations and only show the best ones. This is known as “p-hacking” or “selection bias” in machine learning.

You have 50 different setups. 49 don’t work. 1 works. You write down the hyperparameters that worked and publish the results. Someone is trying to copy you by using the same hyperparameters. But they get different results. Why?

The original author might have had to use a random seed selection bias to get those results. The original author may have spent a lot of time looking for the “right” seeds to make their method stand out. To make a fair comparison, all methods should be tested with different random seeds, and the results should be shown as statistics (mean, standard deviation) instead of just choosing the best run.

Barrier #6: The Library and the Environment Have Different Versions

This is an easy but hard one. You trained a model with TensorFlow 2.5 and CUDA 11.2. Someone is trying to copy your work with TensorFlow 2.9 and CUDA 12.1.

Changes happen in libraries. The default settings are different in each version. Improving algorithms. Things change how they work. When you multiply matrices, they use different libraries behind the scenes.

A study that compared TensorFlow, PyTorch, and LightGBM as ML platforms found that they all give different results, even when they use the same algorithm. It’s also true that different versions of the same library don’t always give the same results.

The answer is easy: use Docker containers to freeze your environment. But in real life, this isn’t always the case.

Barrier #7: The price of computers

It costs between $1 and $3 million and takes months to train a large language model from scratch. That’s not an overstatement. Most researchers can’t afford to get the same results as SOTA for transformer-based models unless they work for a big company.

People don’t trust you because of this. You have to trust that GPT-4 can do what it says it can, but you can’t check it out yourself. You trust what the business says.

Part 3: A Real-Life Example of How Good Intentions Can Go Wrong

Let’s look at a real-life example because it’s better to see it in action than to just read about it.

The Political Science Machine Learning Problem

Researchers at Princeton decided to redo four famous studies that used machine learning to predict what would happen in politics. All four papers had been published in well-known journals. All four said that ML was a lot better than traditional statistical methods.

This is what they discovered:

In Paper 1 (Muchlinski et al., 2016), the researchers trained a random forest model and subsequently compared it to logistic regression. They said that random forests were much better than logistic regression at AUC, which is a common way to measure how accurate something is.

When researchers at Princeton tried to repeat the work, they found that the test set had been messed up. The authors added missing values to both the training and test sets at the same time. This leaked test-set information into the training process, which made the model seem better than it really was.

The answer: The random forest model worked almost exactly like logistic regression after it was fixed. The reported 0.14 difference in AUC went down to 0.015, which is so small that it could be noise.

Paper 2 (Wang, 2016): The same thing happened again. The so-called cutting-edge ML method didn’t work as well as basic statistical models when used correctly.

The cost: These papers changed the way people talked about policy and the direction of future research. People made progress by using these results. They suggested using more machine learning methods. It was all built on shaky ground because the original method had a big mistake that no one saw during peer review.

This doesn’t mean the researchers did anything wrong; they weren’t trying to trick anyone. These are little mistakes that happen when you’re under a lot of pressure to publish and meet tight deadlines, and you’re more focused on getting results than on making sure the paperwork is perfect.

Part 4: Why This Matters (It’s Not Just About Academic Purity)

Okay, so it’s not easy to say again. Why should you care about more than what you learned in school?

Trust and safety in systems that are in use

You need to be sure that an ML model will work when you use it in the real world. Reproducibility lets you:

When production performance drops, fix the problems.

Make sure the fixes worked and didn’t cause any other problems.

If something goes wrong, go back to a state you know.

Show new people how to use your model.

When you have to explain the choices your model made during regulatory audits,

If you can’t get the same results as last week, good luck explaining to a lawyer or a regulator how your model works and why it made a certain choice.

Working together as a group

Groups look into machine learning. You’re stuck if one person can’t copy another person’s work. You can’t make it bigger. There’s no way to make it better. You can’t do other things while you work on it.

Big teams spend days or weeks trying to figure out why people on the same team get different results with setups that are supposed to be the same.

Using up resources

Every time someone can’t reproduce their previous work and has to start over from scratch, you waste computer resources. Some estimates say that the ML community loses billions of dollars every year because of duplicate calculations, experiments that don’t work because they were built on bad foundations, and researchers who spend time fixing problems instead of coming up with new ideas.

The Field’s Trustworthiness

The field loses credibility when 70% of researchers can’t get the same results as those that were published. When people give money, they start to wonder. People who work in the field aren’t sure if they can trust benchmarks that have been published. People from different fields who work together aren’t sure if ML research is as strict as it says it is.

In science, being able to repeat an experiment is very important. You aren’t doing science if you don’t have it. You’re doing alchemy.

Part 5: How to Make Your ML Work Repeatable

Let’s get to work now. This is how to fight back against the problem of reproducibility.

1. Put random seeds all over the place, but don’t think that’s enough.

First, remember that this is only the start and not the whole answer:

import random

import numpy as np

# bring in torch

import tensorflow as tf

# Get the seeds ready

random.seed(42)

# Set the seed for randomness to 42.

torch.manual_seed(42)

torch.cuda.manual_seed_all(42)

tf.random.set_seed(42)

Add this to make the GPU act a certain way:

torch.backends.cudnn.deterministic = True

# torch.backends.cudnn.benchmark is set to False.

But remember that this often makes training take longer because GPUs can’t do as much optimization.

2. Use MLflow and Weights & Biases to keep track of your experiments.

Watch everything. And I mean everything.

You can log with tools like MLflow:

Hyperparameters

At the end of each epoch, metrics

Things that the model made

Data about the environment

Time to learn

Hardware specifications

By keeping track of your experiments in a systematic way, you create a history that you can look up. By comparing them, you can see which hyperparameters worked best. You can repeat any experiment by looking at the exact logs.

MLflow lets you put experiments into parent and child runs, which is great for tuning hyperparameters because each trial keeps track of its own parameters and results.

3. Version Your Data and Models (DVC)

Versioning code with Git isn’t enough. Data changes. Models change.

Data Version Control (DVC) works with Git to keep track of the different versions of your code, datasets, and models. Git doesn’t store big datasets with DVC. Instead, it stores checksums and metadata in .dvc files that Git keeps track of.

This is how the work will go:

dvc add data/training_data.csv

# Add data/training_data.csv.dvc to git.

# "Add training data v1" is what you need to do to commit in git.

People can now see the exact version of the data that was used at the time of an old commit. You can look up metrics for each version to see how the model’s performance changes over time across data versions.

4. Document Metadata As If Your Life Depends On It

Make a list of steps for each experiment that shows how to do it again:

Information about the dataset, such as where it came from, how many samples there are, and what the features are

Steps for preprocessing: what changes to make, how to normalize the data, and how to handle missing values

The model’s structure includes the sizes of the layers, the functions that make them work, and the plan for getting it going.

The learning rate, optimizer, batch size, number of epochs, and validation strategy are all things that affect training.

The GPU model, CPU, RAM, and CUDA version are all hardware.

Different versions of the library, Python, and the framework

Random seed: The exact seed(s) that were used

Results: Error bars for the train, validation, and test sets’ metrics

The date and time of the experiment

One tool that can help with this is model cards (Hugging Face standard).

5. Docker lets you make your environment the same every time.

Not every computer is set up the same way. Docker lets you stop your environment:

FROM pytorch/pytorch:2.0-cuda11.8-runtime-ubuntu22.04

WORKDIR /app

COPY requirements.txt .

RUN pip install -r requirements.txt

COPY . .

CMD ["python", "train.py"]

This Docker image gives everyone the same environment, with the same OS, Python version, and library versions.

6. Use Reproducibility Checklists (Get Ideas from Conferences)

The best conferences now need reproducibility checklists. This is what they talk about:

Are datasets available to everyone?

Can anyone see the code?

Is the description of the algorithm easy to understand?

Have you set the hyperparameters?

Are there random seeds?

Are the requirements for computing clear?

Do the results have error bars or confidence intervals?

Fill these out before you send them. Even better, fill them out before you give them to your coworkers.

7. Also, don’t just give point estimates; give report statistics too.

Don’t say, “Our model was right 92.5% of the time.”

The report said, “Our model got 92.5% ± 1.2% accuracy (mean ± std over 5 runs with different random seeds).”

The second one tells us if your result is good or if it depends a lot on a lucky start. It’s more honest, and it’s easier to repeat because someone else can look at your means and standard deviations and see how they compare.

8. Use deterministic algorithms whenever you can.

Some algorithms have versions that don’t always give the same result. Pick deterministic versions:

XGBoost can always run the same way, but some things are still random.

Don’t use operations like multi-head attention in distributed settings where determinism is important.

Some loss functions don’t always have the same backward passes on GPUs.

This isn’t always possible. It is not possible to have a neural network that is not random. But if you can choose, go with determinism.

Part 6: Tools and Workflows That Actually Work

Let me show you how to use some of these tools together in a real-life situation.

The Full Reproducible ML Stack:

MLflow for keeping track of tests

DVC for keeping track of different versions of data

Docker for keeping environments the same every time

Git for keeping track of different versions of code

A list of things to do to make your README reproducible

This is how they work together:

my-ml-project/

├── data/

│ ├── raw/

│ │ └── data.csv.dvc

│ └── processed/

│ └── features.csv.dvc

└── models/

│ └── best_model.pkl.dvc

├── notebooks/

│ └── experiment_log.md

├── src/

│ ├── train.py

│ ├── evaluate.py

│ └── preprocess.py

├── Dockerfile

— requirements.txt

dvc.yaml

— .gitignore

README.md, which has a list of things to do to get it working again

When you do an experiment:

MLflow keeps track of metrics and hyperparameters.

DVC keeps track of what version of the data was used.

Git keeps track of which code changes caused the results.

Docker makes sure that the environment is the same.

Your list keeps track of everything else.

You or someone else can do the following later:

git checkout <commit-hash>

dvc check out

docker build -t ml-experiment .

# Run ml-experiment python train.py in Docker.

And get the same results byte for byte.

Part 7: What Companies Are Doing About It

Big tech companies have learned these things. This is what they are up to:

Google: Uses its own tools to take pictures of entire environments, such as code, data, dependencies, and hardware specs. They can make copies of their models inside their own company, but they don’t often tell the public about this.

Meta: When they can, Meta publishes papers that have code and data in them. They tell their team members to write down everything they do and use reproducibility checklists.

OpenAI: They put out technical reports that explain in great detail how they train their biggest models, but they also say that it is often impossible to make billion-parameter models again.

Academic Leaders: NeurIPS, ICML, and AAAI are some of the conferences that now require reproducibility checklists and encourage people to send in code. If some papers meet certain standards, they can get reproducibility badges.

There is a clear trend: being able to reproduce your work is becoming a must for getting hired, getting published, and proving that you are a serious professional.

Part 8: The Argument Over Reproducibility (And Why “Reproducibility Alchemy” Doesn’t Work)

There is a legitimate critique that warrants consideration: certain individuals assert that an obsession with reproducibility may hinder exploration, contending that machine learning differs from physics—exact reproducibility may not represent the optimal objective.

The argument is that “In real science, you use new methods and samples to replicate. It’s not as important to get the same results every time.”

This is partly true. Real scientific reproducibility is about whether the same results happen in different situations, not whether you get the same 92.537% accuracy on the same dataset twice.

But first, you need to be able to reproduce it exactly. You can only be sure that the results are true in other situations after you have made sure that you can get the same results again.

Ali Rahimi’s criticism of “alchemy” wasn’t that we should strive for precision to 16 decimal places. People can’t even run the code and get the same ballpark results at the R2 or R3 level, which is why ML research is often not reproducible.

People often say that “ML is too complex for exact reproducibility” to explain why their documentation is bad, not because it’s a real problem.

Conclusion: It’s Your Turn

ML’s ability to have babies isn’t perfect. GPUs will still be hard to predict. Libraries will still be different. Someone will still forget to write something down.

But the best part is that you can control your own work.

You can put seeds in the ground. You can use MLflow. DVC lets you keep track of different versions of your data. You can write down everything that goes on in your experiments. You can share your code and data with other people. You can run more than one experiment and give statistics instead of point estimates. You can put your surroundings in a box.

Will it take longer? Yes. Do you need to take more time to think about what you’re doing? Yes, of course. Will it let you do your work again? Yes.

And the best part is that the things that make your work easy to copy also make it better. You will find bugs faster. You’ll have a better understanding of how your own models work. You will be able to fix problems in production faster. Your team will be able to work together better.

Not only science needs to be able to be repeated. It’s about making ML systems that actually work.

You can either help solve the problem or make it worse.

Key Points

Over 70% of researchers have not been able to get the same results as those that have already been published. In fact, 50% can’t even get the same results as their own work from a few weeks ago.

There are many reasons why reproducibility fails, including not having enough documentation, GPU non-determinism, random variability, data leakage, hyperparameter selection bias, library version changes, and computational barriers.

Real research has been shared with serious flaws (like data leakage) that were only found out when people tried to reproduce it.

There are four levels of reproducibility, from R1 (just a description) to R4 (a full experiment with a full environment).

Using Docker to control the environment, setting seeds, tracking experiments with MLflow, versioning data with DVC, using reproducibility checklists, and reporting statistics over point estimates are all useful ways to do things.

At the best ML conferences, you now have to fill out reproducibility checklists and submit code as a matter of course.

Call to Action

You should be able to do your next ML experiment again. Pick one of the tools from this post and use it at work this week if you haven’t used MLflow or DVC before.

After that, use a checklist to write down what you did in your experiment so that you can do it again. Share what you found with others. Give out your code. Help end the reproducibility crisis by doing one experiment at a time.

Have you had trouble with reproducibility? What has worked for you? Please tell us about your experiences in the comments so that we can learn from each other’s mistakes and fewer people will have to make them.

Are you ready to build ML systems that can be used again? Start with small steps, keep track of everything, and make changes as needed. The ML community will be thankful.

FAQ’s

Q1: Do you just need to set random seeds to make sure that things can be done again?

A: No. It’s important to set random seeds (using Python’s random.seed(), NumPy’s seed, or PyTorch’s manual_seed), but that’s not enough, especially when training on a GPU. GPUs are not deterministic because of the way they order floating-point operations in parallel computations. Different runs on the same GPU can give you slightly different results, even if the seeds are set correctly. To get full determinism, you also need to turn on deterministic modes in PyTorch (torch.backends.cudnn.deterministic = True) or TensorFlow. But this can make things take longer.

Q2: Why do different versions of the same library give different answers?

A: Libraries change over time. Developers change how operations are done, improve algorithms, change the default settings, and update the numerical libraries they use. Matrix multiplication might start with BLAS and then switch to a library that works better. The order of operations in a neural network might change to make things run more smoothly. Version 2.5 and version 2.9 might not be the same. That’s why pinning versions (putting exact library versions in requirements.txt or environment files) is so important for making things work again.

Q3: What is the difference between being able to replicate something and being able to reproduce it?

A: Reproducibility means getting the same results when you use the same code, data, and environment. When you use different methods, data, or experimental designs, replicability means checking to see if the same general conclusions are still true. Science needs to be able to be repeated, but that’s not all it needs. You need reproducibility to make sure your experiment was good, and then you need replicability to show that your results work in other situations. The “reproducibility crisis” is mostly about not being able to reproduce, not about replicability issues.

Q4: Is it worth the extra work to make exploratory research possible to repeat?

A: Yes, for sure. You might think that strict documentation is too much for the exploration phase. But you need to know exactly how you got to where you are as soon as you find something interesting and want to build on it. Keeping track of experiments, keeping track of different versions of data, and writing down decisions are all examples of reproducibility practices that pay off when you find something worth doing. The good news is that many tools, such as MLflow, were designed to add as little extra work as possible to your existing workflow.

Q5: What should I do with research data that is private or sensitive and can be repeated?

A: You can use data version control (DVC) with secure remotes, make fake datasets that have the same statistical properties as your real data, or share your preprocessing steps in detail without sharing the real data. A lot of the best ML papers get around this by sharing code, hyperparameters, and enough procedural details for someone with similar data to do the same thing. List the reasons why data can’t be shared and what needs to be done to make it possible to reproduce it if access is given. Federated learning or secure multi-party computation is how some groups solve this problem.